Leverage Ratio Passively Increases, Innovative Approaches Emerge in...

Leverage Ratio Passively Increases, Innovative Approaches Emerge in Macroeconomic Governance

By ZHANG Xiaojing, LIU Lei and CAO Jing

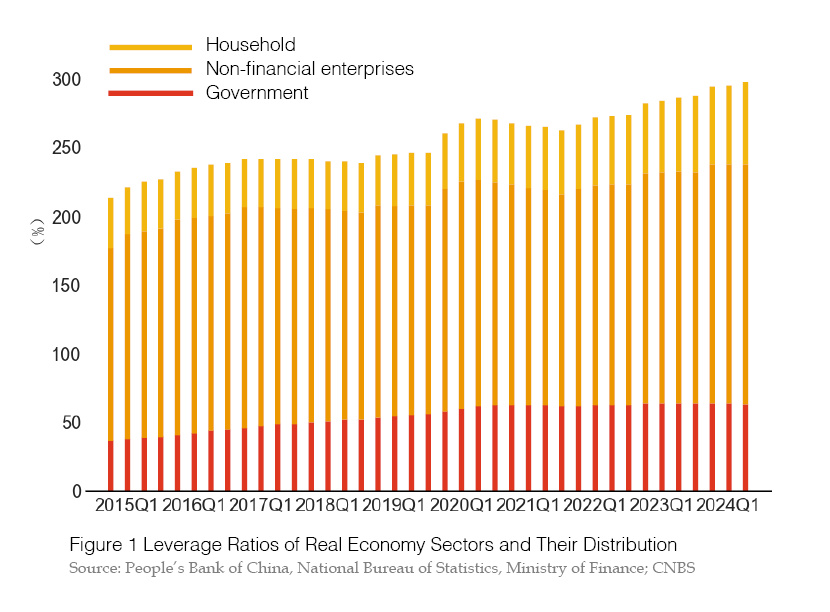

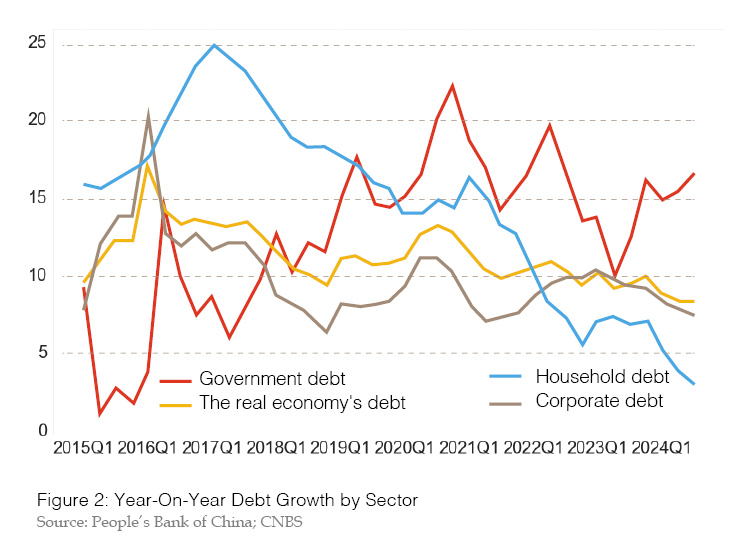

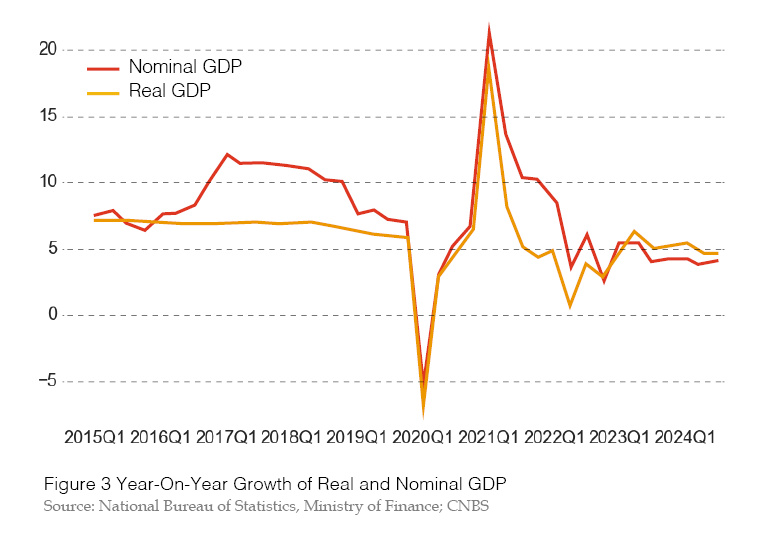

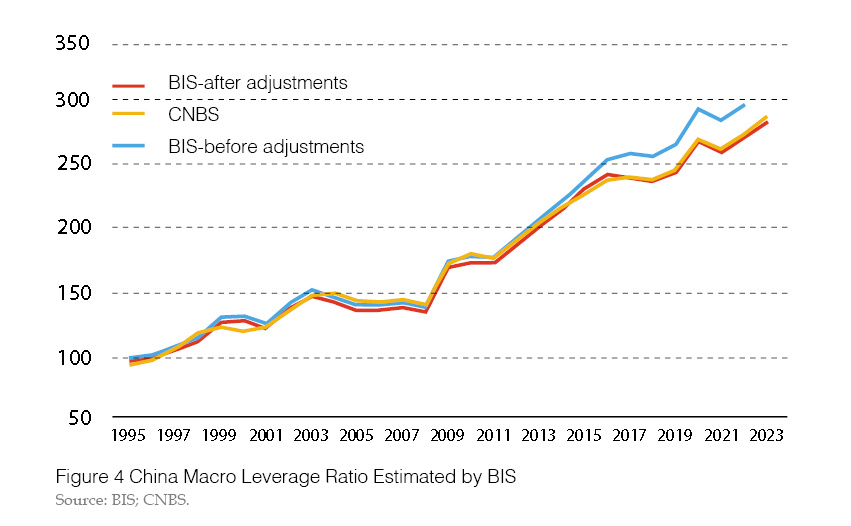

In the third quarter of 2024, the macro leverage ratio of China increased from 295.6% at the end of the second quarter to 298.1%, representing an increase of 2.5 percentage points. Accumulating an increase of 10.1 percentage points over the first three quarters, the growth rate of the real economy’s debt fell to an all-time low of 8.1%. However, slower nominal GDP growth led to a passive increase in the macro leverage ratio. From a sectorial perspective, the household leverage ratio has declined for two consecutive quarters, with mortgage loans experiencing negative growth for six quarters, which is particularly noteworthy. Meanwhile, non-financial corporate leverage remained stable, indicating subdued financing demand. Government borrowing peaked in the third quarter, with government leverage rising by 2.5 percentage points, but the growth rate of fiscal spending declined. Notably, in June 2024, the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) substantially revised its estimates of China’s macro leverage ratios since 2014, with adjustments reaching approximately 20 percentage points for most years. The BIS adjustment trend to Research Center for National Balance Sheet of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CNBS) data reinforces the reliability and authority of our macro leverage estimations, dispelling criticism of potential underestimation compared to international datasets.

Passive Increase in Macro Leverage Ratio

During the third quarter of 2024, the macro leverage ratio increased by 2.5 percentage points, reaching 298.1% from 295.6% at the end of the previous quarter. Specifically, household leverage declined slightly, falling by 0.3 percentage points to 63.2%. Conversely, non-financial corporate leverage and government leverage rose 0.3 percentage points to 174.6% and 60.3%, respectively (see Figure 1).

The growth rate of the real economy's debt remained low. In the third quarter of 2024, the overall debt growth rate fell to an unprecedented low of 8.1% year-on-year, with household, corporate, and government debt rates at 3.0%, 7.4%, and 16.6%, respectively (see Figure 2). While household and corporate debt growth hovered near historic lows, government debt was the key driver of overall debt growth.

Nominal GDP growth remained low. Real GDP grew by 4.6% year-on-year in the third quarter of 2024, while nominal GDP grew by just 4.0%, with a GDP deflator of -0.6%. Since the second quarter of 2023, the GDP deflator has consistently been negative, with nominal GDP growth lagging real GDP growth for six consecutive quarters (see Figure 3). The macro leverage ratio, defined as the ratio of debt size to nominal GDP, tends to rise passively whenever debt growth outpaces nominal GDP growth, regardless of how debt growth declines.

From a sectorial perspective, household leverage declined by 0.5 percentage points in the second quarter and 0.3 percentage points in the third quarter. This contraction in household leverage is cause for concern. In the third quarter of 2024, the overall growth rate of household loans fell to 3.0%, with consumer loans—including mortgages and general consumer loans—dropping to 0.4%. Mortgage loans continue to show negative growth for six consecutive quarters, starting in the second quarter of 2023. Personal business loans also slowly gradually, growing by 9.9% year-on-year in the third quarter. With the implementation of a comprehensive package of real estate financial measures, the trend of “low loan growth, high deposit growth” in household balance sheets is expected to shift, promoting a steady increase in household leverage ratio.

The leverage ratio of non-financial enterprises, after a significant rise of 5.7 percentage points in the first quarter of 2024, remained stable over the subsequent two quarters. The slower growth of corporate debt, especially loans, has tempered the rise in leverage. Both policy and lending rates saw significant cuts in the third quarter. However, due to insufficient corporate investment confidence and the “water squeeze” effect of financial data, the growth rate of corporate loans at the end of the third quarter declined to 9.9%, dragging down the growth rate of corporate debt to 7.3%. Looking at deposits, the growth rate of corporate deposits at the end of the third quarter fell to -3.0%, with time deposits growing by 4.1% and current deposits decreasing by 18.4%. The widening gap between business time growth rates and current deposits reflects the inadequate transmission of monetary expansion to real economy activity.

The government leverage ratio has increased significantly, rising by 4.2 percentage points in the first three quarters of 2024. The central government leverage ratio increased by 2.0 percentage points from 23.8% at the end of 2023 to 25.8%, while local government leverage rose by 2.2 percentage points from 32.3% to 34.5%. The issuance of local government special bonds accelerated in the third quarter, but the increment in fiscal deposits exceeded that of the previous year, which indicates that the intensity of fiscal expenditure has weakened, and the utilization of special bond funds still requires amplification.

BIS Leverage Data Converge with CNBS's Estimates

Currently, the Institute of International Finance (IIF), the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) regularly publish macro leverage ratio data on various countries. IIF’s quarterly data, often lacking in accuracy, often require adjustments based on BIS releases. BIS provides quarterly data for the macro leverage ratios of 30 countries by sector, serving as a crucial resource for timely macroeconomic analysis of financial risks and academic study. The IMF publishes annual data, covering a wider range of countries, making it valuable for cross-border analyses. Domestically, China’s macro leverage ratios are primarily estimated and released by the CNBS, as estimates from the People's Bank of China are not disclosed regularly. Compared to the BIS, which typically lags by half a year, CNBS releases data with a delay of no more than two months, allowing for timely insights into evolving conditions and early identification of macro-financial risks. More importantly, CNBS has refined the quality of its data beyond BIS, producing a more accurate reflection of China’s true macro leverage levels.

Firstly, CNBS eliminates double counting in the total leverage of the real economy, especially between local governments and non-financial enterprises. BIS adopts the general government leverage ratio data published by the IMF, which includes the debt of local government financing vehicles (LGFV). Since LGFVs’ debts are also attributed to non-financial corporate debt, adding the two together will inevitably expand the overall leverage ratio level.

Secondly, when estimating non-financial corporate leverage ratios, BIS tends to overestimate shadow banking debt which encompasses diverse financing forms and makes it difficult to apply a uniform method of estimation. However, CNBS has a clear definition of shadow banking debt in its estimate, and does not include the parts of fake equity, unlike BIS’s broader statistical scope.

In June 2024, BIS made substantial adjustments to its estimates of China’s macro leverage ratio since 2014, with adjustments reaching approximately 20 percentage points for most years. Notably, the adjusted BIS data closely aligns with past estimates provided by CNBS, indicating a convergence with our figures (see Figure 4). This development highlights the reliability and authority of CNBS macro leverage data, dismissing the criticisms that suggest potential underestimations in favor of relying solely on international data. Moreover, CNBS data, which tends to be published one to two quarters ahead of BIS, provides more up-to-date market analysis, obscuring the opinions of financial analysts.

Policy Recommendations

China's economic fundamentals remain robust, with a large market, strong resilience, and significant potential. However, in recent years, the economy has encountered new challenges, mainly due to insufficient domestic demand. During periods of economic contraction, economic entities tend to adjust their behavior, reduce spending and adopt a "debt minimization" approach to restore their balance sheets. In this context, effective functional finance should serve macroeconomic balance, exhibiting a marked countercyclicality to mitigate the contractionary effects on micro entities' balance sheets. Nevertheless, due to factors such as annual budget constraints and tax assessment systems, China’s fiscal policies tend to exhibit pronounced pro-cyclical characteristics. As downward pressure on economic growth increases, these procyclical fiscal policy measures further weaken domestic demand and maintain low price levels, negatively affecting synergy with other growth stabilization policies.

Pro-Cyclical Fiscal Policy Impedes Balance Sheet Recovery

Procyclical fiscal policy is not conducive to recovering private sector balance sheets and improving social expectations. Private sector credit expansion is an endogenous factor in macroeconomics, characterized by a clear cyclical tendency that depends on the exogenous driver of fiscal expansion. With countercyclical fiscal policy measures, timely government spending can restore confidence among households and enterprises, transforming consumer spending and business investment into increased household income and corporate profits, thereby entering a new cycle of prosperity. However, if governments adopt procyclical fiscal policies, the economy may face increasing downward pressure and fall into a "balance sheet recession".

Firstly, during economic downturns, insufficient government spending dampens current revenues and future expectations for the private sector. On the one hand, in order to complete the revenue budget, fiscal authorities tend to impose overhead taxes or overdraw the tax contributions of state-owned enterprises, adding further hardship for households and businesses. Data from the 2022 national public budget show that total tax revenue only achieved 92.5% of the budget, while penalty revenues reached 113.9%, and state capital operating revenues exceeded 243.9% of the budget. On the other hand, reduced revenues have led governments and state-owned enterprises to cut costs through measures such as salary reductions. The burden of repaying local government debt remains high, resulting in delayed payments for public sector expenditures, including salaries and contract payments.

Secondly, faced with a decline in current and projected revenues, the private sector will actively restore its balance sheet by reducing spending and liabilities, which in turn will lead to further deterioration of the balance sheet and ultimately falls into a "balance sheet recession". While China has yet to show clear signs of such a recession, indicators of distress are evident. Despite lower financing costs, private sectors willingness to actively fund remains weak. The transient rise in earnings and profits in 2021 only led to accelerated debt repayments rather than increased investment. Currently, household debt growth has reached an all-time low, while non-financial corporate debt growth is also below 10%. According to general trends in financial cycles, the expansion of private sector credit tends to correlate strongly with rising asset prices, while contractions in debt financing and falling asset prices compound the difficulties faced by private sector balance sheets.

International Comparisons Reveal Significant Fiscal Expansion Potential

With the rise of modern monetary theory, many countries have shifted from classical balanced budgets to functional finance aimed at achieving full employment, resulting in rising deficits and government leverage ratios without triggering sovereign debt crises. For instance, to counter the impact of the pandemic, major Western developed countries have implemented large-scale fiscal stimulus policies. The US has a fiscal deficit ratio of 14.7% in 2020. Japan achieved the same fiscal ratio in 2021, and remained above 5% until 2023. From a volatility perspective, since 1996, the fiscal deficit ratio of the has fluctuated between -2.3% (indicating a fiscal surplus of 2.3%) and 14.7%, and the fiscal deficit ratio of Japan has fluctuatedbetween 3.5% and 14.7%.

Historically, China has maintained its fiscal deficit ratio in the range of 1.6% to 4%, a relatively modest level of variation. In 2023, due to an additional issuance of 1 trillion yuan in special-purpose treasury bonds at the end of the year, the fiscal deficit ratio climbed to 3.87%, the highest level recorded in nearly two decades. However, this figure remains significantly below the deficit ratios of the US and Japan over the same period, indicating that China's fiscal policy still has considerable room for expansion, and the countercyclical regulation needs to be strengthened.

Strengthening Fiscal Expansion to Support Balance Sheet Recovery

In late September, a comprehensive set of incremental policies was introduced, focusing on stabilizing asset prices and alleviating debt pressures. This approach balances stock adjustments with flow controls, emphasizing efforts to stabilize the real estate market and strengthen capital markets, thus helping to restore as balance sheets across various sectors, highlighting the important innovation in macroeconomic governance. The continuous effectiveness of financial policy combinations is promising, and we expect even stronger fiscal expansion policies. In the short term, there must be a stronger countercyclical adjustment of expenditure. In the long term, macroeconomic governance must shift focus from annual equilibrium to a greater emphasis on intertemporal balance.

Firstly, the central government deficit should be expanded to more than 4%. As households and businesses recover, incremental fiscal policies in 2024 need to maintain the necessary strength of government expenditure. Breaking the implicit limit of a fiscal deficit ratio of 3% and increasing the central government leverage ratio is the best choice, which not only demonstrates a commitment to countercyclical fiscal management, but also helps to stabilize private sector expectations promptly.

Compared to special purpose treasury bonds, general treasury bonds are less restrictive in use and less risky, which is more conducive to promoting economic growth.

Secondly, fiscal policy must shift from revenue-oriented measures, such as tax reductions, to expenditure-oriented policies that provide subsidies to low- and middle-income groups. Currently, insufficient private sector confidence limits the effectiveness of large-scale tax cuts, which also reduce tax revenues. Countercyclical macroeconomic adjustments require stabilizing of the overall tax burden and ensuring the government financial capacity. Given the prevailing issues of weak domestic demand and high youth unemployment, providing subsidies to low- and middle-income households not only promotes consumption but also helps to bridge the wealth gap, enhancing the stabilizing role of fiscal policy. The central government should increase investment in essential public services, including pensions, childcare, education, health care, and affordable housing, alleviating the concerns of these income groups.

Thirdly, fiscal balance should shift its focus from an annual mindset to an intertemporal one. A medium-term fiscal budget compatible with economic cycles should be established, together with improved macroeconomic forecasts, in order to make effective use of budgetary adjustment funds. Greater flexibility in fiscal objectives is needed, avoiding the imposition of overhead taxes and advance taxes during economic prosperity while allowing for a hands-off approach to wealth accumulation during economic downturns. Additionally, exploring a national macro balance sheet management model aligned with economic cycles would enable the government to expand its balance sheet during economic downturns, address challenges posed by stagnant or contracting private sector balance sheets, and facilitate rebalancing of macroeconomic balance sheets.

ZHANG Xiaojing is Director of Institute of Finance & Banking, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences / Director of National Institution for Finance & Development LIU Lei is Secretary-General of China National Balance Sheet Research Center, National Institution for Finance & Development

CAO Jing is Associate Researcher of Institute of Finance & Banking, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences