Analysis on the Possibility of European Debt Crisis and Its Influence

Author: SUN Mingchun and YANG Yixuan

As a result of one of the most severe energy shortages in half a century,high inflation has returned to Europe. With the European Central Bank (ECB) starting to raise rates to combat inflation,many investors are worried that another Eurozone (EZ) sovereign debt crisis will soon arrive. We doubt such risk is imminent. Being equipped with a new crisis-fighting tool,in addition to the tools,programmes and experiences accumulated since the last crisis in 2011,the ECB should be able to scare bond market speculators away and keep the public debt market under control.

That said,the real risk lies in the private sector. With no end in sight for the Russo-Ukrainian war,persistent natural gas shortages may cause severe disruption of EZ economic activities,which may force business closures and job cuts,give rise to defaults and bankruptcies,and even cause a private credit crisis. In face of such a crisis,member state governments would have no choice but to provide fiscal aids to alleviate the pains of the private sector. Massive fiscal bailout would put more burden on EZ governments and exacerbate their fundamental imbalances,possibly triggering a public debt crisis that even the ECB cannot handle.

To forestall such a vicious cycle,European policymakers need to resort to fiscal unity to solve the debt sustainability issue once and for all. Additionally,perhaps more importantly,the European Union (EU) needs to build a mechanism to achieve energy security to further reduce the risk of energy shortages and the ensuing economic disruptions. With a proactive ECB maintaining financial stability and a more coordinated,synchronised EU energy policy that guarantees at least the minimum amount of natural gas for each EZ country to survive the winter,EZ should be able to sail through the storm.

Energy shortages and high inflation

The current round of European troubles began with natural gas shortages. For over a decade,natural gas has been a reliable,affordable and relatively clean energy source for European countries,with a wide range of use as both raw chemical material and heat source for industries and households,essential for northern European countries with cold winters. However,Europe’s over-reliance on Russian gas and the energy-intensive nature of key European industrial powerhouses (especially Germany) means that any major interruption of natural gas supply could cause severe disruption in economic activities as well as high inflation.

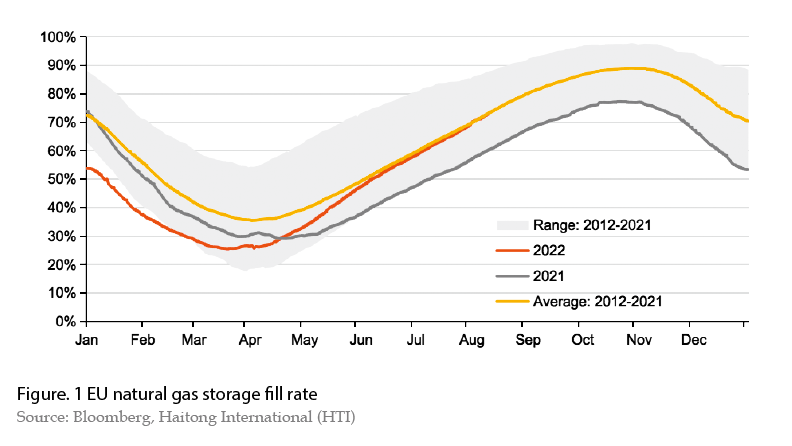

Unfortunately,such risk is becoming more pronounced today. Even before the start of the Russo-Ukrainian War,rising geopolitical tensions between European Union (EU) and Russia had led to reduced Russian supply,as the fill rate of European gas storage in 2021 dropped to the lowest level since 2009 (see Figure 1). Supply was further reduced in 2022,with Germany’s Nord Stream I gas pipeline running at 40% capacity even before the annual maintenance period in July and only 20% afterwards,forcing European countries to drastically increase liquefied natural gas (LNG) import from elsewhere.

Moreover,there are limited ways to solve the problem. The potential substitute LNG is mostly imported from the US and the Middle East,particularly Qatar. But there are two main supply constraints: limited supplier production capacity and limited LNG processing ability in EZ countries where pipeline gas supply has been disrupted the most. A decade of under-investment in the energy sector made a massive increase in production in short notice very difficult. Even though Qatar has already started developing a new natural gas field in 2021,the project may take another year or two to finish.

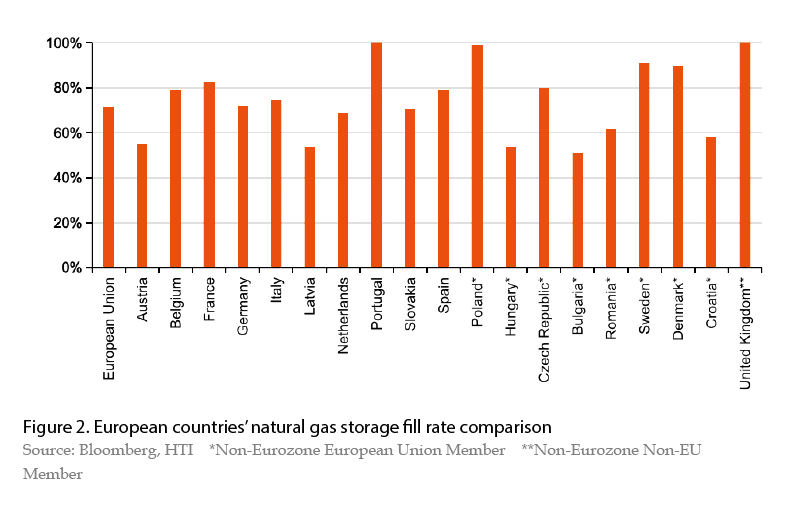

EZ also faces the scarcity of LNG terminals,especially in countries with traditionally high pipeline gas dependency,such as Germany and Italy. Germany has been trying to secure more supplies from the Middle East and borrowing floating LNG terminals to process imports. The lack of LNG sharing scheme among EU members is also not helping,as evidenced by the substantial divergence in their natural gas storage fill rates (see Figure 2).

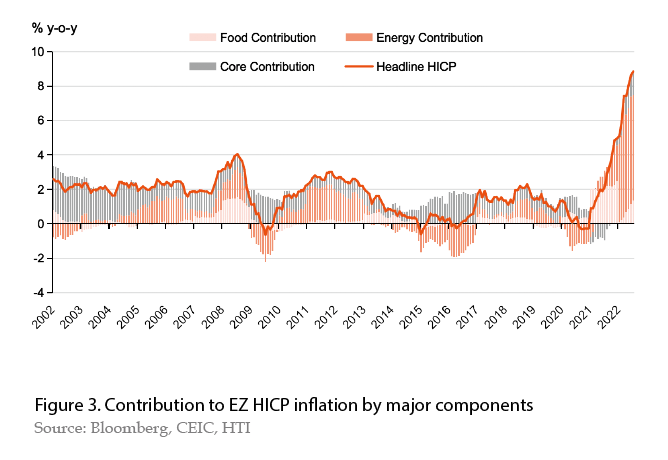

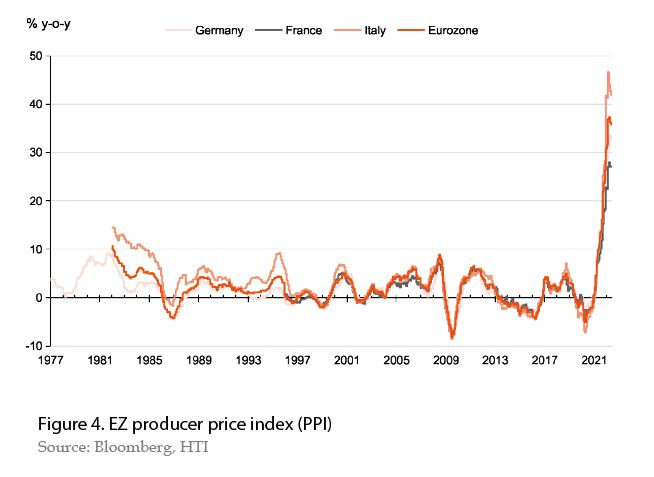

Such scarcity induced a seemingly unstoppable rally in European benchmark gas price (Dutch TTF forward contracts). Since the end of 2020,one-month TTF forward price has increased almost eightfold by the end of July,with a peak rise of 1650% in March 2022. As a result,EZ consumer price inflation (HICP) reached 8.9% on a year-on-year basis in July (see Figure 3),with energy component (weighted 11.3% in HICP basket) making an outsized contribution of 69% (6.1 percentage points) to overall inflation. Producer price inflation among EZ countries also skyrocketed to levels not seen since the 1970s,reaching 20%-50% for different states over the past months (see Figure 4).

Policy tightening and the risk of a sovereign debt crisis

To combat inflation,the ECB raised policy rates by 50bp in July,2022. Nevertheless,rate hikes might not be effective in fighting inflation this time as they primarily affect the demand side of the economy. EZ’s energy-driven inflation is mostly caused by supply-side factors,which the ECB has no control over. EZ’s non-food,non-energy “core” inflation is 3.3% on a y-o-y basis,but only contributed 1.4 percentage points (or 16%) to the 8.9 percentage points rise in headline HICP inflation.

Even though rate hikes might not be effective in containing energy inflation,the ECB nonetheless has to tighten policies to keep inflation expectation in check. Labour cost growth reached 3.8% year-on-year in the first quarter of 2022,the second highest in 10 years. The number of news reports on European labour strikes and pay disputes also rose significantly in June to the third highest in 10 years,highlighting rising inflation expectations and increased pressure of wage inflation. For these reasons,the market is expecting more hikes from the ECB. As of August 12th,Euribor futures are pricing around 130bp of additional rate hikes by the year-end (a total of ~180bp in 6 months). Such an aggressive pace of tightening was never seen for the ECB since its establishment.

During the previous tightening cycle in 2011,the ECB’s hasty rate hikes debatably exacerbated EZ sovereign debt crisis. Market participants are wondering whether the current tightening cycle will invite another Eurozone Sovereign Debt Crisis.

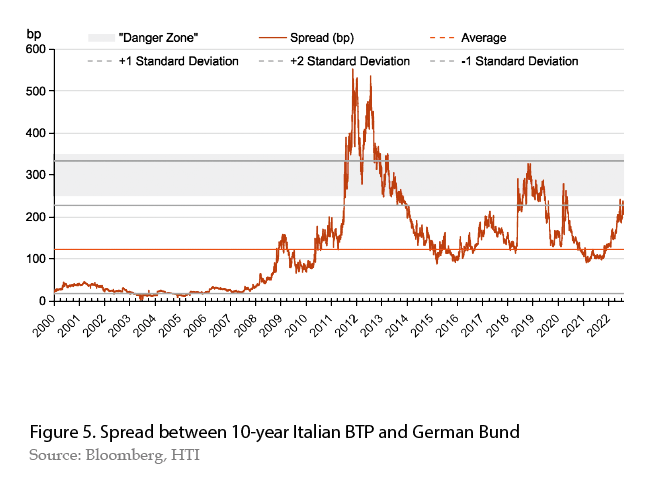

One of the major concerns associated with rate hikes is that,if sovereign borrowing cost (reflected by bond yield) rises too much,EZ governments may find it difficult to re-finance their debts,causing solvency risk to spike and bond yields to rise even more. Market participants are closely monitoring such risks,especially as one of the key sovereign risk metrics,the spread between 10-year Italian BTP and German Bund,surged over the past months,breaching 230bps and inching closer to the market implied “danger zone” of 250-350bps (see Figure 5).

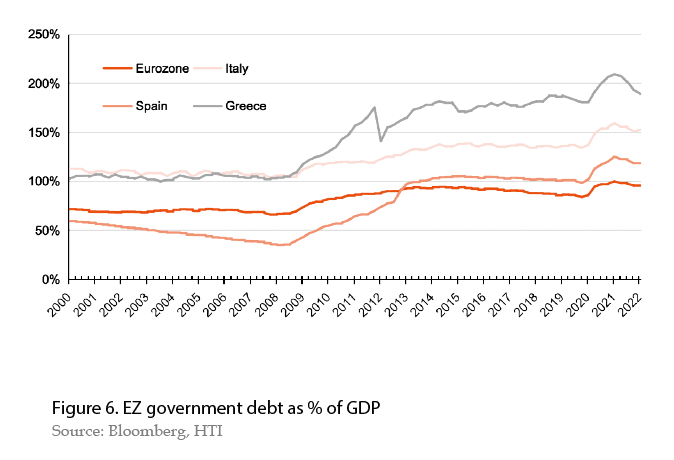

This risk is more prominent for Southern European countries,such as Italy,Spain,Portugal and Greece. Since last Eurozone Crisis,their fiscal condition has not improved. In fact,due to massive COVID-related fiscal spending,government debt to GDP ratios for these countries are universally higher today than 11 years ago (see Figure 6).

To reduce the risk in sovereign bond market,the ECB has introduced a new open-ended crisis-fighting tool: Transmission Protection Instruments (TPI). Using flexible reinvestment of maturing securities under Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme (PEPP),the ECB can intervene the sovereign bond market whenever needed without necessarily expanding its balance sheet. The eligibility of securities under TPI,the value of reinvestment or new net investment committed,and the criteria for deploying the tool,are all intentionally left ambiguous. This gives the ECB sufficient discretion to intervene in the bond market in times of distress.

Since rate hikes are necessary and EZ countries’ fiscal imbalances are not going away,the pace of hiking and the effectiveness of the anti-fragmentation TPI is what stands between an ordinary hiking cycle and a crisis.

If the ECB decides to raise rates gradually,it can still show its inflation-fighting determination and protect central bank credibility,while keeping speculative forces in check in the sovereign bond market. As paced tightening would only have marginal effect on market liquidity,peripheral countries’ re-financing cost could be kept steady. Under such circumstances,the TPI would not need to be deployed. The tool can be considered as an open-ended forward guidance,similar to Draghi’s “whatever it takes” announcement and the introduction of Outright Monetary Transactions. By devising the TPI,the ECB tries to convince the market is that,if something goes wrong,an unlimited backstop will be deployed to deter speculations.

If the ECB follows the hiking trajectory priced by the market and embarks on the most aggressive tightening in its history,the market may react rather negatively to the point where ECB intervention is necessary. In this case,the ECB can deploy TPI pre-emptively and close core-peripheral sovereign spreads before distresses turn into a crisis. The flexible nature of TPI means that the ECB would have unlimited fire power if market condition worsens further. The crisis could be avoided as speculators normally won’t fight against a committed and credible central bank.

Most likely,a sovereign debt crisis can be avoided in the short-term. But EZ’s macroeconomic imbalances will likely stay. Inflation may come down gradually in 2023 due to base effect if energy prices stop rising at current pace. However,prolonged rises in consumer and producer prices,especially for staple goods,have led to a sharp decline in real income and a higher recession risk. Both household and business activities may stagnate due to higher costs and insufficient rises in wages and profits. Unemployment rate may rise and consumer confidence would plummet. As inequality worsens,even social unrests might arise.

A different kind of crisis

Although the risk of an imminent EZ Sovereign Debt Crisis is limited,a real income shock and the subsequent worsening of household and corporate balance sheets do not bode well for private credit markets. A further reduction of natural gas supply,if happens,could trigger a severe slowdown in economic activities,forcing many corporates into severe losses and even bankruptcies. Household finance may deteriorate too. Such private credit distress may cause considerable damages to the banking sector,leading to a crisis that the ECB would find difficult to handle.

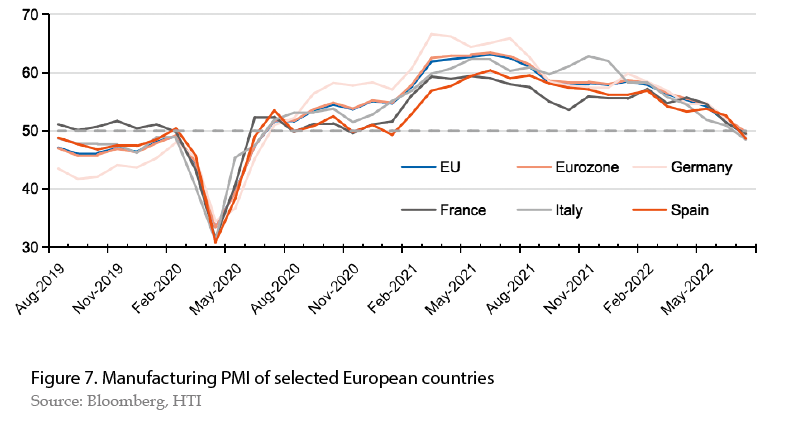

The negative effect of gas shortages has already emerged,as evidenced by manufacturing PMI for the Eurozone as well as for many member states dropping below 50 in July (see Figure 7). Industry-wise,energy-intensive manufacturers are among the most fragile if natural gas supply were to become scarcer. With some industrial equipment,plants,and systems designed to be compatible only with natural gas as the heat source,electricity supply from other sources (wind,solar,even thermal coal and nuclear),even if available,cannot keep the systems operating. Some companies may have to cease operation permanently,even filing bankruptcy,if natural gas supply were so low that it has to be rationed. Reduced production of key materials may cause collateral damages to upstream and downstream sectors,further threatening EZ’s economic outlook.

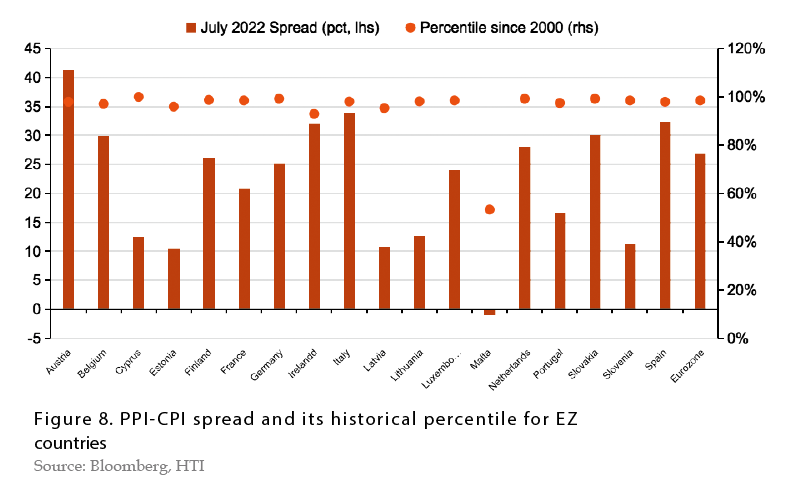

In addition,disproportional rises in input costs relative to consumer prices are suppressing business margins. If the gap between PPI and CPI inflation remains for a prolonged time,firms’ operating losses may be so large that they may become insolvent (see Figure 8). For example,some fertiliser producers and chemical manufacturers may incur substantial losses if they have to pay benchmark prices on all their natural gas consumption. Energy and electricity utility companies are also suffering,since the price of natural gas and electricity provided to households are capped under long-term contract prices,significantly lower than input costs. In face of heavy losses,nationalisation is coming back to life. For example,German energy provider Uniper is actively seeking nationalisation after almost draining its credit lines; French electricity company EDF is re-nationalised after posting huge energy-price induced losses.

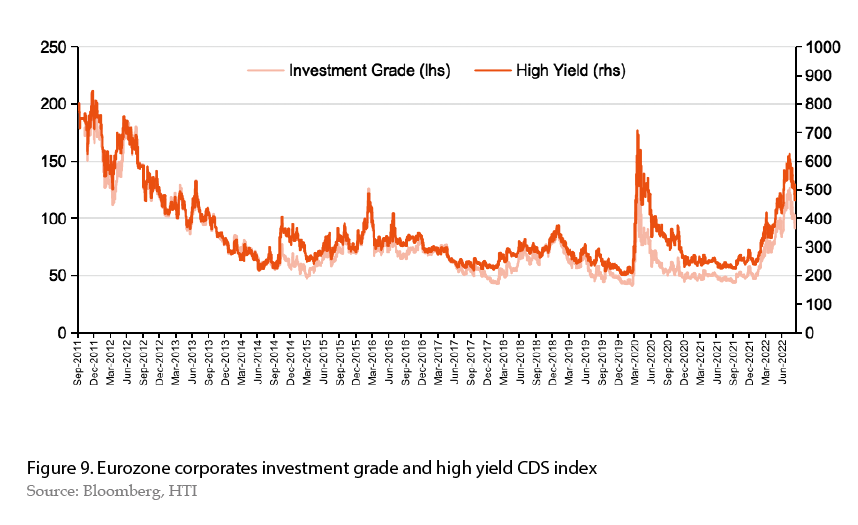

Severe losses,business closures and bankruptcies in the corporate sector will surely affect the credit quality of EZ commercial banks. For large corporations,their default risks,as represented by Markit iTraxx Eurozone Investment Grade CDS Index and High Yield CDS Index,have spiked in recent months (see Figure 9). For smaller companies,after months of operational difficulties,they may find it hard to pay back loans and gradually build up a stock of non-performing loans for commercial banks. Closure of businesses would also lead to a rise in unemployment. With inflation staying elevated,falling real income may cause deteriorations in household finances which would threaten the quality of banks’ balance sheet too.

Fiscal support and structural reforms

If natural gas shortages drag EZ into recession and evolve into a full-blown private credit crisis,the ECB has few options to respond. The ECB had purchased corporate bonds before,but were limited to investment grade,not high yield or non-rated bank loans. Since the energy shock may affect small- and medium-sized firms disproportionally due to their limited cost pass-through ability and weaker balance sheets,their distress,mainly in the high yield space or in the form of bank loans,cannot directly benefit from ECB’s bond purchases. The case is similar for household debts. Though banks have access to ECB liquidity directly,the deterioration of their asset quality would not be mitigated much by monetary easing.

Therefore,fiscal policies would be crucial to alleviate the pains of the fallout of the private credit crisis. Firstly,individual EZ countries can introduce targeted relief towards households and businesses,in the form of energy price subsidies or forgivable government-guaranteed loans,to mitigate the negative real income shock and prevent defaults. Secondly,collective EZ relief funds from Next Generation EU (COVID-19 recovery),REPower EU Plan (energy security),or European Stability Mechanism (financial stability) can be utilised to provide additional fiscal support for EZ national governments. Finally,EZ governments can also collaborate with the ECB to establish some private sector refinancing programmes,like the Main Street Lending Facility created by the Fed during the COVID-19 shock in 2020.

However,the risk of doing too little and too late on the fiscal side cannot be under-estimated. Long-held belief of fiscal conservatism in European politics might be a major obstacle for timely deployment of fiscal reliefs in time of crisis. Differences among EZ countries’ economic fundamentals,political stance,and policy priorities may also limit the effectiveness and scale of coordinated EZ fiscal supports.

On the other hand,if deployed,such fiscal supports may push EZ countries’ sovereign leverage further up and make government finances even less sustainable in the long-run. With policies returning to crisis-fighting easing mode,the Euro could depreciate further,fuelling imported inflation and worsening EZ’s term of trade. Stagnating economy may cause deepened political divide and incite social unrest,which may lead to a rise in anti-EU and anti-Euro sentiments,threatening the very existence of the Euro and the European Union.

From a longer term perspective,European policymakers need to resort to structural reforms to forestall such a vicious cycle. EZ governments need more fiscal unity to solve the debt sustainability issue once and for all. Additionally,perhaps more importantly,the EU needs to build a mechanism to achieve energy security to further reduce the risk of energy shortages and the ensuing economic disruptions. Today,European unity is what they need the most. With a proactive ECB maintaining financial stability and a more coordinated,synchronised EU energy policy that could guarantee at least the minimum amount of natural gas for each EZ countries to survive the winter,EZ should be able to weather through the storm.

SUN Mingchun is the Chief Economist of Haitong International Securities Group Limited (HTI) and a member of China Finance 40 Forum

YANG Heinrich is a Macro Analyst at HTI